Giorgos Seferis | Mythic History (Part II)

that death has unexplored paths

and its own justice

that when we die standing on our feet

in the brotherhood of stone

unified by cruelty and weakness,

the old dead would break away from the circle and rise

smiling in a strange calm.

X

Our land is closed, mountains all around

that are crowned day and night by a low sky.

We have no rivers, we have no wells nor water springs,

only a few cisterns, and even they are empty; they echo and we worship them.

It is a flat hollow sound, just like our solitude

just like our love, just like our bodies.

It seems strange that long ago we managed to build

our houses, our sheds and our pens.

And our weddings, the fresh wreathes and the caressing fingers

become riddles that remain inexplicable to our soul.

How did our children get born, how did they grow?

Our land is enclosed

by the two black Colliding Rocks. On Sunday

when we walk down to the port seeking relief

we see illuminated in the sunset

broken planks from journeys that have not ended

bodies that no longer know how to love.

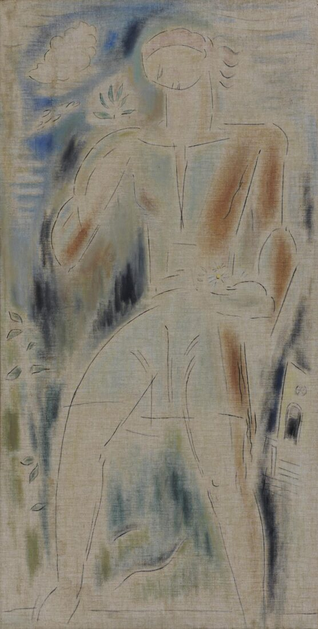

if it is to know itself

must look

within a soul:

the stranger and the enemy we saw in the mirror.

The shipmates were good fellows, they did not complain

either out of exhaustion or out of thirst or out of cold,

they assumed the manner of the trees and the waves

withstanding the wind and the rain

withstanding the night and the sun

without changing with change.

They were good fellows, for days and days

they sweated at the oars – eyes cast low

breathing rhythmically

and their blood flamed red under their subdued flesh.

At times they sang, eyes cast low

when we sailed past the empty island with the fig trees

in the west, beyond the cape of

the barking dogs.

If it is to know itself, they would say

it must look within a soul, they would say

and the oars would strike the golden sea

in the sunset.

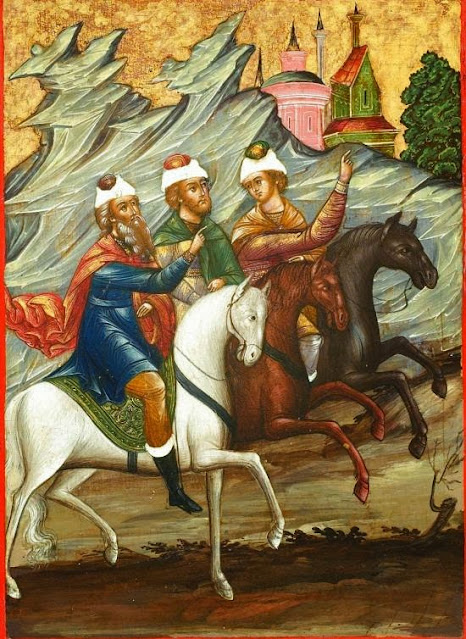

We sailed past many capes, many islands, the sea

that begets another sea, seagulls and seals.

Wretched women would at times lament

their lost children

and others would in rage seek Alexander the Great

and past glories submerged in the recesses of Asia.

We anchored off coasts where night fragrances and bird song

filled the air, where the waters stirred in their flow

memories of a great happiness.

But there was no end to the journeys.

Their souls became one with the oars and the locks

with the austere face of the bow

with the rudder’s foamy trail

and the water that distorted their visage.

The shipmates all passed away one by one,

eyes cast low. Their oars

mark their resting place on the shore.

No one remembers them. Justice.

But Greek philosopher Dimitris Liantinis prefers to view the Argonauts of Seferis’s poem as heroic figures; symbols of courage, boldness and bravery in the face of inevitable defeat by a harsh and indifferent cosmic fate and I must say I find this reading quite attractive. For Liantinis then, the Seferian concept of Justice in ‘Argonauts’ acquires an ontological rather than a moral meaning, akin to the notion of Justice we find in Anaximander or Heraclitus; an ultimate principle that ensures balance in the general cosmic economy of beings. In such a system, in which the death of one being becomes the gain of another, human beings are no more or less provileged than a tree, the wind behind the sails or a distant star. Freed from any human moral encoding that Seferis imposes, argues Liantinis, the Argonauts become part of the cosmic order of things [3].

Such a portrayal of the Argonauts as fearless explorers of undiscovered regions is also echoed by Friedrich Nietzsche in The Gay Science. But for Nietzsche, these modern-day travellers have little interest in homecoming, enthralled as they are by the wonders of the journey.

Seferis was, of course, a keen reader of D. H. Lawrence’s 'Last Poems', which contain some lovely verses about the sea. And often, even before he'd had his coffee and toast for breakfast, Lawrence would imagine the Argonauts sailing by ... "They are not dead, they are not dead!"

ReplyDelete