Giorgos Seferis | Mythic History (Part I)

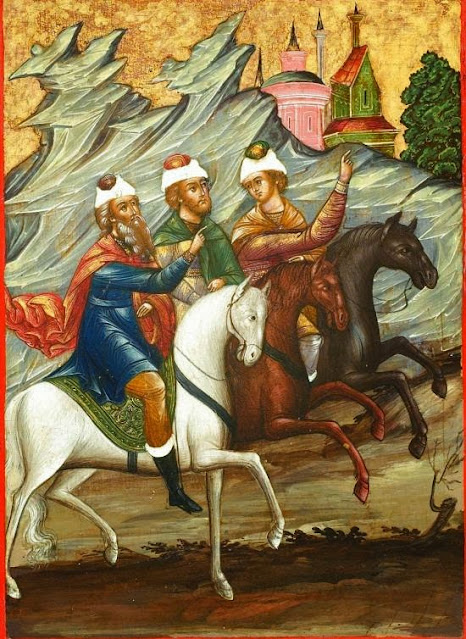

Konstantinos Parthenis, 'Angel' (post-1940)

If, for Yiannis Ritsos, the work of the poet should reflect his engagement with history, projecting a politicised image of the artist as a public persona seeking to interpret and furthermore cultivate a response to historical reality, the poetry of his contemporary Giorgos Seferis proposes a somewhat different viewpoint, one that derives from a fictional (and mythical) universe populated by solitary figures. Paradoxically, it was one of the latter's poems, “Denial”, set to music by Mikis Theorodakis, that epitomised for the Greek nation the struggle for freedom. Seferis’s funeral in 1971 turned into a mass demonstration againsts the repressive regime of the dictators and a lament for a life that, in the poet’s words, had begun “with such feeling, such force, with such desire and passion” and had gone bitterly wrong.

Born in Smyrna – a prosperous, commercial city in Asia Minor with a thriving Greek population – in 1900, the son of a lawyer, and later a professor at the University of Athens, Giorgos Seferis was educated in Athens and Paris. While a reluctant student of law at the Sorbonne, he became acquainted with French contemporary poetry, and especially the work of the Symbolists. At the same time, poetic composition was occupying a central position in his thought and life: “From sunrise to sunset,” he wrote in a journal entry, “I think of nothing else except art”. Throughout his life, the conflict between the demands of artistic expression and those of what he called “a practical life”, his diplomatic service, was to prove a constant source of anguish:

At times I feel the urge to buy a plot and cultivate it without materialistic concerns … What a strange notion I have, and how it differs from that of others, of the poetry of our times … I would spend my life reciting my poems to myself, without even writing them. I can probably understand Baudelaire’s hatred for printing, and I even remember a saying of ‘my friend’ Laforgue ‘poems, what a strange word, something one writes to escape boredom and please his friends’.

Seferis’s identification of the oral with the authentic betrays an idealist position in that it assigns “the origin of truth … to the logos”. Such a position also characterises his attitude to poetry, which he sought to reconstruct and revitalise through the imaginative use of Greek tradition. Thus, history and myth are intermingled, everyday characters parade through the poems alongside mythical personae and symbolic figures, a modern landscape forms the stage upon which unfold fragments of an ancient story. But it is the past that persistently re-asserts itself against a stark present which offers little or no prospect for renewal. As for the poet, he is left to contemplate in desolation a shattered life that can only impart a tragic sense of human existence.

Mythic History

IX

IX

The port is old, I can wait no longer

for the friend who left for the island with the pine tree

or the friend who left for the island with the plane tree

or the friend who left for the open seas.

I press my fingers over the rusty canons, over the oars

for my body to spring into life and make a choice.

The ship’s canvases give out only the smell

of salt from a bygone storm.

If I wished to remain alone, it was to seek out

solitude, not to seek out solace,

the shattering of my soul on the horizon,

these lines, these colours, this silence.

The night stars evoke Odysseus'

anticipation of the dead amidst the asphodels.

And here amidst the asphodels, when at last we cast anchor, we wished to find

the ravine that saw Adonis wounded.

The poetic voice articulating the terms of the journey is a solitary voice: the poet in exile, an insignificant onlooker of the major historical events unfolding before his eyes. The sacking and burning of Smyrna by the Turks in 1922 signified for Seferis, as for the Greek nation, the end of the so-called “Grand Ideal”: the restoration of Greece to the glory of the past and its resurgence as a powerful, modern state. The sense of loss informs the poet’s attempt to reconstruct - albeit in vain - this ideal through the medium of his art.

I

It was the angel

we were awaiting intently for three years

watching closely

over the pine trees, the seashore, the stars.

Becoming one with the plough’s blade or the ship’s keel

we kept looking for the first seed

so that the age-old drama would commence anew.

We returned to our homes broken

with frail limbs, our mouths ravaged

by the taste of rust and sea-salt.

When we awoke we travelled north, like strangers

immersed in a flurry of pure white feathers from the swans that tormented us.

On winter nights the strong easterly wind maddened us

in the summer we sank deep in the agony of interminable days.

We brought back

these bas-reliefs of a humble art.

(My translation ~ January 2007, May 2024)

Notes

The two poems are from the collection Mythic History (in Greek, Μυθιστόρημα) published in 1935. You can read the Greek text here.

This and the posts on Seferis to follow were part of a literary talk titled 'George Seferis: And what of the poet...?' and presented at a private salon in London in February 2007.

Comments

Post a Comment